VISITOR GUIDE

THE AMALFI ARSENAL

MUSEUM OF THE

COMPASS AND THE

MARITIME DUCHY

—

The exhibition

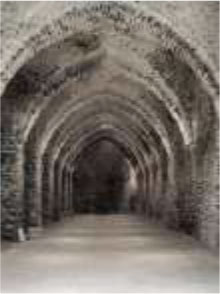

The Arsenale di Amalfi houses the collections of the Museum of the Compass and the Maritime Duchy, which document the city’s history dating back over a thousand years and the debt owed by the modern world and European civilisation towards the civitas, the heirs to the tradition of Rome. Archaeological finds, codices and parchments, ancient coins, nautical instruments: the splendid spaces of this imposing medieval building are home to a wide range of relics, many of which tell the story of some of Amalfi’s innovations and the great contribution that this coastal population made to Italian and Mediterranean history. The visit begins in the first aisle on the right, one of the lanes of the old shipyard where warships were once built. On display here are priceless archaeological finds from the Roman and medieval periods, salvaged from the seabed or brought back by ancient sailors who travelled along the coasts of the Tyrrhenian Sea. The second aisle is dedicated to the golden age of the ancient Maritime Republic, which later became a Duchy, in the period from the ninth to the twelfth century. Ancient codices and parchments document how the “city-state” of Amalfi operated and the progress it made in terms of law and the organisation of society. Of particular note is the Tabula de Amalpha, the first collection of laws governing nautical matters in Italy. This codex of maritime law remained in force throughout the Mediterranean until the sixteenth century. Also of interest are the examples of tarì, a coin struck by the Amalfi mint that was accepted in all the main ports in both the East and the West. The historical galleon in the centre of the aisle symbolises the contests, both ancient and more modern, between Amalfi and the other maritime republics of Venice, Genoa and Pisa. The exhibition ends with a series of nautical navigational instruments, including the compass, which the sailors of Amalfi were the first in the West to use. They improved and perfected it, revolutionising navigation techniques and opening up ocean routes to the “New World”.

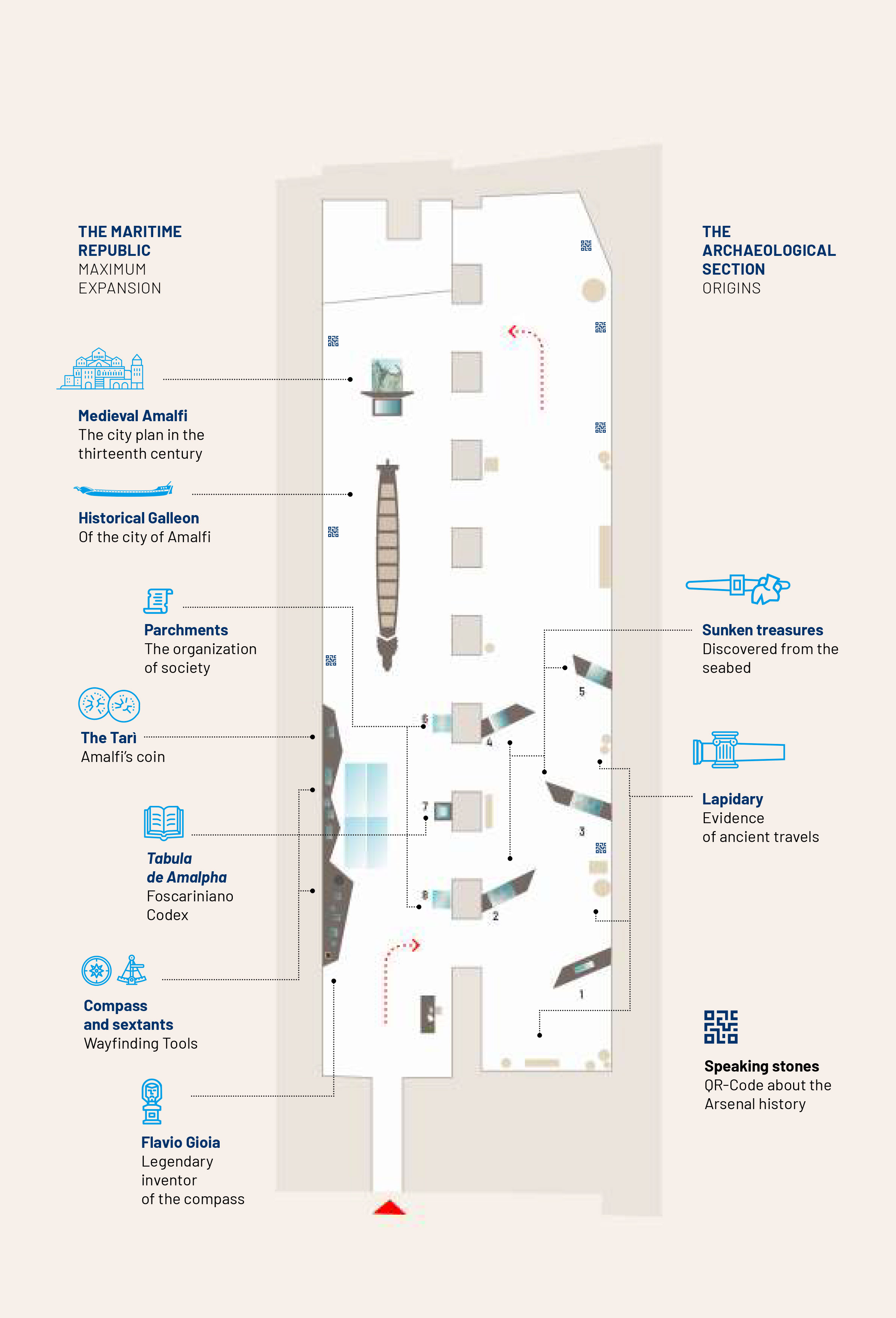

The Arsenal The Amalfi Arsenal is the symbolic monument of the ancient maritime power of the town. Documented as early as 1042, it is the only medieval shipyard in the West that can still be visited and is largely preserved in its original structure.

ORIGINS

Roman Amalfi

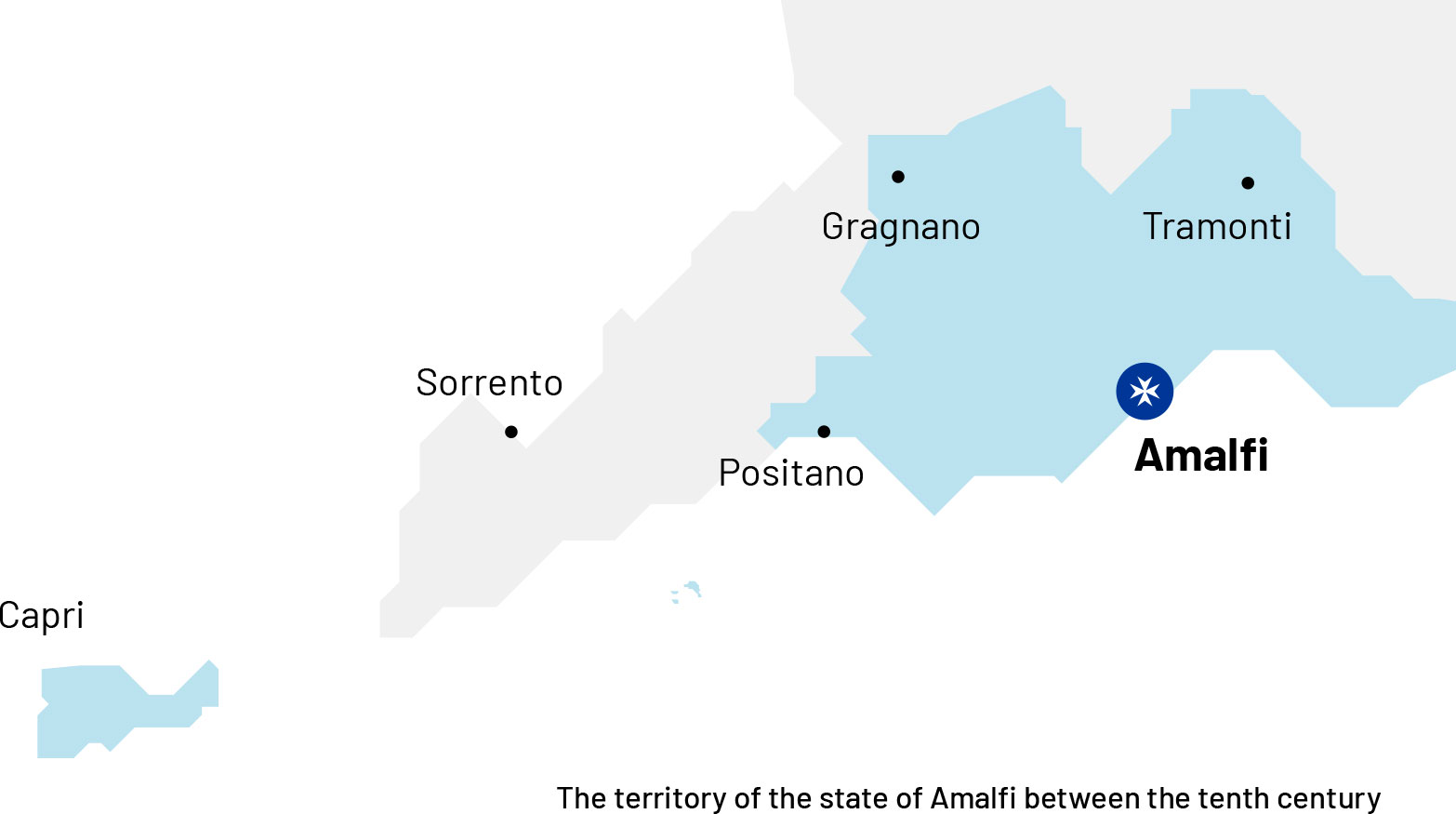

The date of the foundation of Amalfi is still shrouded in mystery, but it was certainly of Roman origin. From the third century BC onwards, cargo ships sailed along the Amalfi coast, as evidenced by some of the exhibits, which were found on the seabed along the coast. The first settlements date back to the first century AD, when wealthy patrician families built their own villas in the most favourable sites along the coast and inland, such as Minori, Positano, Tramonti, and Amalfi itself. The first concrete information we have about the city dates back to 591, when the marine village of Amalfi became a defensive stronghold (castrum) of the Byzantine Duchy of Naples, to defend its own borders from the advancing Lombards. Overlooking the sea and protected by the mountains, the small town grew rapidly, and became a refuge for many families fleeing from other parts of the region, which had fallen to the barbarian hordes. Thanks to its strategic position, Amalfi was transformed, in a very short time from a village to a city, and became a bishopric as early as 596. Under the Byzantine government the coastal population learned to defend itself from foreign invaders, expanded its naval fleet, and made alliances with neighbouring cities, becoming increasingly self-sufficient from an economic and productive point of view.

SUNKEN TREASURES

DISCOVERIES FROM THE SEABED

Most of the archaeological finds on display here come from the seabed off the coast of Amalfi: evidence of how transport ships frequented these shores – an obligatory waypoint on their navigation routes – as early as the Roman era. Some of the most striking finds include Sicilian, Eastern and Arabian containers and amphorae, confirming the direct relations between Amalfi and the other Mediterranean territories.

The birth of the Republic

Amalfi was administratively separated from the Duchy of Naples on 1 September 839, known as the “Byzantine New Year”, to form an independent republic. It kept its autonomy for about three centuries, collaborating with the Byzantines to defend itself from the ambitions of the Lombards based in nearby Salerno. While remaining under the formal protection of the Byzantine Emperor, the city gained de facto freedom that grew stronger and stronger, allowing the entire region to prosper and expand. Thanks to its fortuitous geographical location combined with the skills of its inhabitants, Amalfi became a well-recognized and powerful entity in the Mediterranean between the ninth and twelfth centuries. The skill of its sailors and its diplomatic sway allowed the Amalfi to spread its influence from east to west, developing profitable economic links that turned the Amalfi Coast into the centre of trade between the Italian world, the Byzantine Empire, and the Arab lands.

LAPIDARY

EVIDENCE OF ANCIENT TRAVELS

The columns, capitals and other architectural elements from the Roman imperial period are probably the result of ancient travels by Amalfi’s seafarers between the eleventh and twelfth centuries. Many of the pieces were shipped by the people of Amalfi to be resold or reused, such as the precious marble sarcophagus from the third or fourth century AD, later reemployed in the thirteenth century as a tomb.

MAXIMUM EXPANSION

From the Republic to a Maritime Duchy

The small city-state of Amalfi was organised politically as a republic, administered by annually elected Counts and later by Prefects. With the passage of time it became more and more royaldynastic in nature, until it became similar to a monarchy in 957, with the establishment of a duchy ruled by Dukes who inherited their power. The evolution of the administrative life of the city was accompanied by a substantial development in the economy, and the growth in wealth and power of the city. First as a Republic and then as a Maritime Duchy, Amalfi was able to maintain good relations with all the peoples of the Mediterranean, expanding its trade routes from Spain to northern Africa, as far as the coasts of Asia. The commercial abilities of the Amalfi were equal to their political skill. In a very turbulent historical period, they were able to make agreements, according to circumstances, with different peoples, including the dreaded Saracens. In the period between the tenth and twelfth centuries, Amalfi experienced its period of maximum expansion, during which it became a commercial and military power that dominated international trade between the East and the West. It developed from a small military stronghold, into a city-state with not only economic but also cultural, artistic and scientific ties with other peoples. Many new splendid public and private buildings were erected in the city centre and its surroundings, which absorbed influences and ideas from the rest of the world. Churches, convents, palaces, and watchtowers created the skyline of a modern and cosmopolitan capital, which welcomed guests from all over the world and amazed its visitors with the beauty and opulence of its architecture and landscape. Along the coast, important buildings were erected that combined ancient Roman knowledge with innovations from the Arab world, such as the splendid Arsenal, in which we currently find ourselves. Much of the port and shipbuilding infrastructure was destroyed by violent tsunamis, such as the one in 1343. The remains of some impressive hydraulic engineering works are still visible under the sea a few dozen metres from the current coastline, a rare and remarkable example of submerged medieval technology.

MODEL OF MEDIEVAL AMALFI

THE CITY PLAN IN THE THIRTEENTH CENTURY

The three-dimensional reconstruction of medieval Amalfi is an important tool in understanding the city’s urban history. Years of study and research were required to create the model and successfully visualise the layout of the city following the golden centuries of the Republic and the Maritime Duchy.

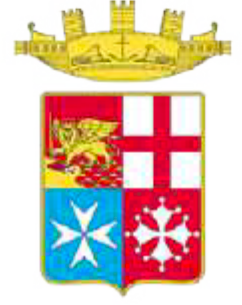

The Maritime Republics

The term “Maritime Republics” refers to certain Italian coastal cities that prospered during the Middle Ages thanks to their maritime activities. The definition generally refers to the most important of these: Amalfi, Pisa, Genoa, and Venice, which dominated the Mediterranean Sea between the tenth and thirteenth centuries. Thanks to their political autonomy, geographical position, and extensive commercial and maritime capabilities, these four port cities were able to gain control of the traffic between Europe, Asia, and Africa, competing with the Byzantine Empire and the Arabs, who until then had had a monopoly of such trade. The development of these great naval powers heralded a new European expansion towards the East after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Their imposing fleets allowed them to control the commercial shipping routes and to defend their cities from the incursions of Saracen pirates, as well as take part in expeditions such as the Crusades. The enterprising merchants of Amalfi, Venice, Genoa, and Pisa gave rise to modern capitalism: they minted gold coins and developed new exchange and accounting practices, laying the foundations of international finance and commercial law. The Maritime Republics also made a fundamental contribution to the development of navigation, encouraging organisational, technological and administrative progress. The Amalfi were responsible for the spread of the compass and the drafting of the Amalphitan Tabula, a maritime code used throughout the Mediterranean until the sixteenth century. The Venetians were responsible for the invention of the large galley. The schools of Genoa and Venice were responsible for much of the nautical cartography of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. This domination by the four cities continued as long as each of them was able to come up with mutually beneficial agreements. Over the centuries, the strong rivalries that would later lead to the decline of Amalfi and Pisa, overwhelmed by the military and political power of Genoese and Venetians, increased. The emblems of the four republics still make up the coat of arms of the Italian Navy.

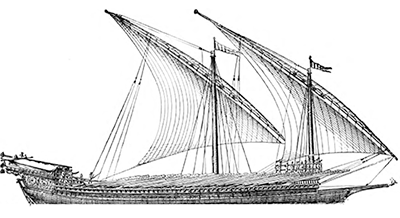

The Historical Regatta The Regatta of the Historical Marine Republics is a race established in the 1950s to evoke the golden age of the cities of Amalfi, Venice, Pisa, and Genoa. The race is held every year in a different city and takes place on reproductions of twelfth century galleons, each one powered by eight oarsmen and steered by a helmsman. It is a very exciting race, very popular with the communities of the four maritime cities, and it attracts a large crowd. A historic procession is the central event of the Regatta. In 1955, the set designer of the Teatro San Carlo in Naples, Roberto Scielzo, designed the set and the costumes of the Amalfi parade.

HISTORICAL GALLEON

OF THE CITY OF AMALFI

The galleon is the historical boat used in the Regatta of the Ancient Maritime Republics. Built entirely from wood, it is around 11 metres long, weighs about 800 kilograms and has fixed seats. It is painted in the traditional blue colour that represents the city of Amalfi and has a winged horse as its symbol on the figurehead. The boat raced until the original wooden galleons were replaced by versions made from more modern and lightweight materials.

The City-State

Banner of the city of Amalfi designed by Roberto Scielzo in 1955. It symbolises the noble origins of the city, as described on the first page of the Tabula de Amalpha.

The maritime and commercial expansion of Amalfi in the Mediterranean region in the Middle Ages was supported by an administrative system that is still considered to be a model of organisation and good governance. The ability of the Amalfi to establish themselves outside their borders was accompanied by the ability to manage their city-state through laws and legal systems, maritime codes and commercial law. These were fundamental to its socio-economic growth, as well as very significant in the history of medieval institutions in the West. The Republic was governed by a legislative corpus of considerable importance, including the Pandette (the Code of Justinian). Amalfi held an original copy from the sixth century, which was stolen by Pisa in 1135. The life of the Amalfi people was regulated by the Consuetudines Civitatis Amalphie, a collection of laws that included rules relating to marriage contracts, citizenship issues and property rights, while also providing interesting insights on women, who had a prominent role in society. The Amalfi people also deserve the credit for having written the oldest Italian maritime statute: the Tabula de Amalpha, also known as “The Amalfi Tables”, written around the eleventh century. It is the first code of the law of the sea to have regulated every aspect of navigation, including the obligations and responsibilities of sailors, and was adopted throughout the Mediterranean area and followed until the sixteenth century. These precious “codes of conduct for coexistence”, some of which are preserved in this Arsenal, are among the many original records found in Amalfi, testifying to how the wise regulation of civil society and its institutions contributed to the social progress and economic prosperity of this community during the medieval age.

PARCHMENTS

THE ORGANISATION OF SOCIETY

These six parchments, dating from between the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries, provide important insights into the political organisation and socioeconomic life of medieval Amalfi. The five oldest parchments are written in Amalfi’s typical curial script, characterised by small shapes, long lines and ornamental flourishes. Over time it became less and less understandable, and it was actually forbidden by Frederick II in 1220, making room for the Gothic Chancery script; the latter was used to draw up the sixth and most recent parchment on display here, dating back to the thirteenth century.

CASE N. 6

Parchment n. 1 1007

Giovanni I Duke A. 31 and Sergio III Duke A. 5, 11 February,

V indiction, Amalfi.

The document refers to a division of property situated

in Atrani, Maiori and Minori, made by brothers of the

noble Atrani family the Gettabetta. In the text there is

a reference to a member of the family absent because

away at sea.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 1. 1007 - 45 A).

Parchment n. 2 Dated between 1053 and 1090

The assignment of a dowry of 225 soldi (= 900 tari)

to a young noblewoman.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 2 - 45 B)

Parchment n. 3 1052

Mansone II Duke A. 10 and Guaimario Duke A. 5, 5 March,

V indiction, Amalfi.

‘Colonìa’ contract stipulated between the convent

of SS. Cirico and Giulitta in Atrani and Orso Docibile

of Stabian territory, for the cultivation situated at

Messigne, near Pompei.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 3. 1052 - 45 C).

CASE N. 8

Parchment n. 1 Dated 18 Feb. 1209 (indiction XII)

Twelfth year of the reign of Frederick II.

Concession of chestnut woodland and a vineyard,

property of the archbishop, located at Nocellito in

Tramonti.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 14 - 45 D).

Parchment n. 2 1012

Sergio III Duke A. 10, 10 May, X indiction, Amalfi.

Contract for the sale of a vineyard situated in the

locality of Ponteprimaro of Maiori, the contractors of

which were of middle class.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 2. 1012 - 45 E).

Parchment n. 3 Dated between 1085 and 1094.

Sale of chestnut woodland located at Novella in

Tramonti.

(Inv. Pergamena n. 5 - 45 F).

Seafaring

Throughout the Middle Ages, Amalfi had a large and powerful military and merchant fleet, which was an ace in the hole for the maritime Republic’s control of the trade routes along the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea. A substantial and well-equipped merchant fleet supported the political and commercial capabilities of the Amalfi. Trading vessels such as the nabidium or buctius spent much of their time on the seas, sometimes staying away for several years, continuously moving between North Africa, Spain, Provence, the Syrian-Palestinian coast, and Asia Minor. Small merchant ships were built along the coasts, in a sort of outdoor shipyard called a scaria. The scarium of medieval Amalfi today lies under the sea in front of the city, where medieval docks and moorings have been discovered. The Amalfi navy maintained an importance equal to that of Naples, remaining at the forefront in the struggles that took place along the southern coasts of the peninsula. The military fleet contributed several times to freeing the Tyrrhenian Sea of Saracen pirates, as in the famous battle of Ostia in 849, which saved Rome from an attack by Muslim pirates. The types of warships of the Amalfians varied over the centuries. Initially, dromones were used, two-storey ships that used a hundred oarsmen arranged in pairs, each with a single oar. Around the ninth century came the sagena, small, fast boats driven by a single Latin sail. In that same century, the galley, a narrow, long and low draught fighting ship, whose name means “swordfish”, after the shape of its hull, made its appearance. To construct the warships, Amalfi built this splendid Arsenal, where we are now. It has been a shipyard in which military fleets were built and repaired for centuries. Their extensive experience on the sea, their political skill, and the need to protect their commercial traffic, drove the Amalfians to draw up laws and regulations to regulate life on the sea. The Amalfi people were among the first to elaborate legal norms on navigation and maritime trade, which around the twelfth century were collected in a single code: the Tabula de Amalpha. The code, also known as Tavole Amalfitane, is the first collection of laws on the rights of navigation in Italy and was used throughout the Mediterranean until the 16th century.

The Battle of Ostia: Raphael, fresco (1514-1515); Vatican Museums, Rome.

TABULA DE AMALPHA

THE FIRST LAWS OF THE SEA IN ITALY

The Tabula de Amalpha was a milestone in the history of maritime law and one of the most important documents in Italian medieval history. For five centuries, it remained the point of reference for anyone sailing in the Mediterranean Basin, thus helping to standardise maritime legislation along the coasts from East to West, including Arabia. Transcribed in around 1132, the Tabula de Amalpha contained a series of rules that regulated everything connected to sailing. The code governed traffic, trade, and the conduct of crew members at sea, attributing specific rights and duties to each of them. It addressed the issue of providing compensation and assistance to injured or ill seamen; it indicated how to act in emergency situations, such as attacks by pirates or ship damage; it tackled the matter of charters and compensation in the event of lost goods, establishing the rights and duties of shipowners. The original version of the Tabula de Amalpha no longer exists. The text survives to this day thanks to handwritten copies such as the one in the Foscarini Codex exhibited here, which contains the most complete version of the code. The codex was discovered in Vienna and purchased by the Italian government in 1929 before being donated to the city of Amalfi.

Codice Foscariniano Manoscritto del XVI secolo Raccolta di fonti amalfitane medievali tra le quali la “Tabula de Amalpha”

[CASE N. 7] This voluminous code contains the complete copy of Tabula de Amalpha, the original version of which has been lost. In addition to the Amalfi Tables, other important medieval Amalfi sources have been transcribed in the volume: the Consuetudines Civitatis Amalphitanie (collection of laws drawn up in 1274); the Chronicon omnium Episcoporum et Archiepiscoporum Amalphitanorum (chronicle of the bishops and archbishops of the diocese of Amalfi from its origins to the 16th century); the Dell’Origine by Longobardi and Normandi; the Challenge of Barletta; the Description of the things of the Kingdom of Sicily written by Alfonso Crivelli; the Report on the things of the Kingdom of England written by Petruccio Ubaldino Fiorentino in 1551. The Code takes its name from the Doge of Venice Marco Foscarini, to whom it belonged.

Trade

GThe Amalfians were among the first and most important architects of a unitary economic system in the Mediterranean, within which goods and people circulated freely, unencumbered by political and religious divisions. The merchants of Amalfi acted as skilled mediators between the Arabs of Africa and Spain, the Byzantine East and the Romanesque-Germanic West, becoming the commercial channel for diametrically opposite civilisations. They were active in southern and northern Italy, and along the North African and Spanish coasts. They were among the first Westerners to go to Syria and then to Alexandria, Cairo, and especially Constantinople, where they had their own neighbourhood, with land, warehouses, a church, and a cemetery, before the Venetians and the Pisans. The business of the Amalfi negotiators was based mainly on intermediation: the Mediterranean peoples were supplied with European products, primarily wood, and they brought goods of Arab and Byzantine origin to the Italian markets. There were numerous routes along which the merchants operated. They exported agricultural produce to the East such as chestnuts, almonds, pistachios, honey, and wheat, as well as Sicilian silk, linen fabrics, and wood. On the homeward trip, in addition to gold received as payment, they brought very fine fabrics, tapestries, spices, pepper, and luxury furnishings. The first great businessmen of the Middle Ages arose in Amalfi society, and many of them accumulated enormous wealth. Some of these were also philanthropists and patrons, contributing to the construction of public works such as the Jerusalem Hospital, which housed the monastic order of St. John, that later became the “Knights of Malta”, whose symbol is the Amalfi Cross.

THE TARÌ

AMALFI’S COIN

The tarì was the official currency of Amalfi for centuries, used widely for trading throughout the Mediterranean. As the dominant force in maritime traffic along the coasts from East to West, the state of Amalfi was given authorisation to mint its own monetary unit around the eleventh century, alongside those already in circulation in the Byzantine Empire, Africa and the Lombard principalities. The Amalfi tarì originated from the Arab currency of the same name, demonstrating the strong trade relations established with the Islamic world. The mint of Amalfi struck coins similar to the Muslim ones, which were then exchanged with other currencies including the Byzantine coin (worth 4 tarì). The Amalfi coin had significant purchasing power: a nabidium (trading ship) was worth 4,000 tarì in 1085; a threestorey house cost 3,000 tarì in 1128; a grapevine pergola of 28 square metres was worth 15 tarì in 1070. The tarì minted in Amalfi contained gold and silver in equal parts, along with small amounts of copper, and weighed 1-2 grams. The first coins were a faithful reproduction of the Arab coin of the same name, featuring Kufic inscriptions with a religious theme on both the front and the back. Over time the original inscription was reproduced in an increasingly corrupt form, becoming nothing more than a decoration; it is thus defined by experts as “pseudo-Kufic”. The return to canonical forms with the addition of the name of the Norman king occurred with William II (1166-1189). The Amalfi mint stopped operating in 1222, when it was closed down permanently by Frederick II.

N. 1 Amalfi Mint-gold tari with pseudikufic arabis

inscription and central globe, on the obverse and

reverse (first half of the eleventh century).

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 13

N. 2 Amalfi Mint-gold tari with pseudokufic Arabic

inscription and pommelé crossmonthe on the obverse

and reverse (last quarter of the eleventh century).

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 14

N. 3 Amalfi mint-gold tari, with pseudokufic Arabic

inscription and central globe on the obverse and

reverse (beginning of the twelfth century).

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 15

N. 4 Amalfi mint – gold tari, with pseudokufic

Arabic inscription, “R” of king Roger II on obverse and

octagon cross on reverse (1140-1154).

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 16

N. 5 Amalfi mint – gold tari, with pseudokufic

Arabic inscription, “R” of King Roger II on obverse and

octagon cross on reverse (1140-1154)

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 17

N. 6 Amalfi mint – gold tari, with pseudokufic

Arabic inscription, “R” of King Roger II and octagon

cross on the reverse (about 1146)

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 17

N. 7 Amalfi mint – gold tari, with pseudokufic

Arabic inscription, “R” of King Roger II and octagon

cross on the reverse (about 1146)

Diametro 13 mm – Inv. 18

Navigation

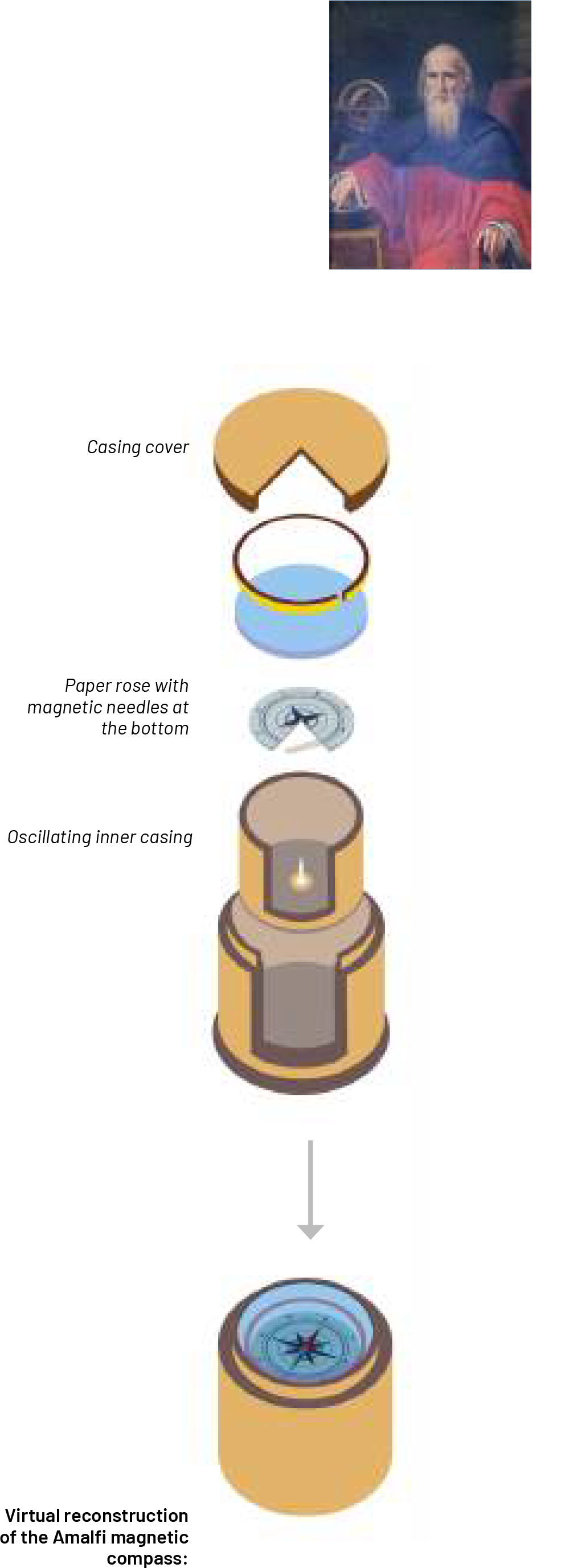

For the ancients, navigation was a necessary activity, but one that was often perilous. The sailors of the past sailed along the coast without ever losing sight of the mainland, a technique that could be used in the Mediterranean but that involved making very long journeys. With the passage of time, they began to use different methods of navigation at sea. They began to use astronomical observations and the first navigational instruments, such as sextants, which had first been used by the ancient Greeks and Romans around the second century BC. The turning point for navigation came with the invention of the magnetic compass around the year 1000, which is attributed to the Chinese and was perfected by the Amalfi. The compass is a tool for identifying the cardinal points that allows you to orient yourself both day and night in any weather conditions. Its operation is based on a magnetized needle that is free to turn on a pin, which aligns along the earth’s magnetic field, indicating the north-south direction. This revolutionary tool has improved navigation by facilitating maritime trade and travel by sea, making it safer and more efficient. Thanks to the magnetic compass, the first “navigation charts” could be produced, which significantly improved geographical knowledge. The compass allowed ocean routes to be opened up and made is possible for Europeans to discover new worlds. Without the compass, none of this would have been possible. Today the compass is still used in navigation in the open sea and more generally in open landscapes where there are no reference points but, in large part, it has been replaced by electronic and satellite technology such as GPS, gyro compasses, radio compasses, and, in cases of emergency, even solar compasses. For centuries, it was thought that the magnetic compass had been invented in Amalfi by Flavio Gioia, but it is now believed that this man probably never existed. However, it is certain that around the middle of the thirteenth century the Amalfians were the first, together with Venetians and Arabs, to import the compass into Europe from China, modifying and improving it to make it

COMPASSES AND SEXTANTS

WAYFINDING TOOLS

Nineteenth-century compasses and sextants from the Nautical School of Amalfi. Sextants were used to measure the azimuth of the stars and thus to establish the geographical latitude.

Flavio Gioia According to tradition, he was a navigator who lived around the twelfth century. The invention or, more accurately, the improvement, of the magnetic compass invented by the Chinese, has long been attributed to him. Some historical research, however, suggests that Flavio Gioia never actually existed and that the origin of the legend was the incorrect translation of a sixteenth-century manuscript. Whether real or fiction, legend or myth, it is nevertheless certain that Amalfi played a decisive role in the history of the compass. It was the Amalfians, sometime before 1300, who added a paper disc with a representation of the famous eight-pointed “wind rose” to a magnetised needle. Not only do the points of the rose remind us of the cross symbol of Amalfi, but the names of the winds describe the direction from which they blow. The Tramontana comes from Tramonti, a municipality north of Amalfi, while the other three winds blow from directions that converge on the Amalfi Coast: the Libeccio from Libya, the Scirocco from Syria, and the Grecale from Greece.

FLAVIO GIOIA

LEGENDARY INVENTOR OF THE COMPASS

Maquette made as a model of the statue of Flavio Gioia located in the square in front of the Arsenale. Alfonso Balzico, 1902 – Bronze sculpture.

“And then there is AMALFI, the most

prosperous town, the noblest for its origins, the

most famous for its living conditions, being the

richest and wealthiest.

Amalfi’s territory borders on Naples, which is a

beautiful town but less important than Amalfi."

Ibn Havqal

Arab traveler and geographer, 977 ca.